In Stone and Story

Early Christianity in the Roman World

Chapter 11: Money & Influence

Photo Gallery

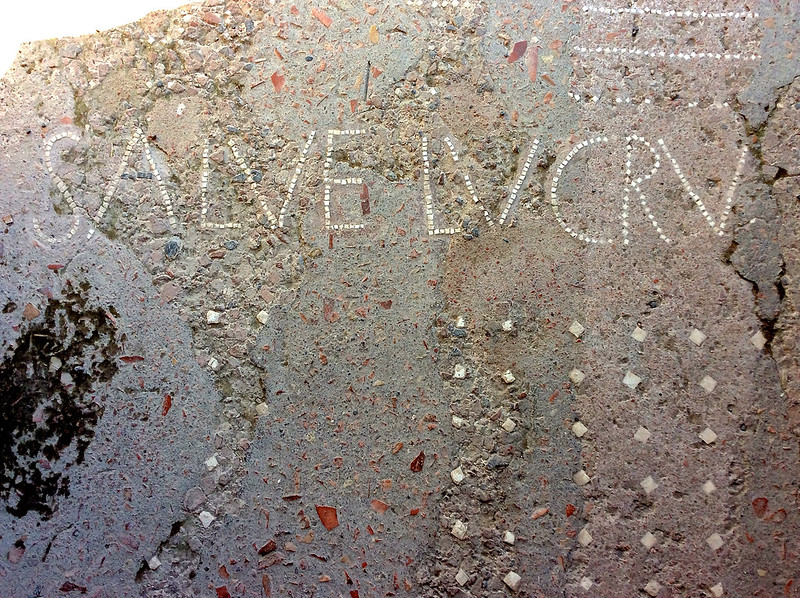

Photo 11.1

People who entered the House of Siricus in Pompeii (7.1.47) were greeted with a slogan embedded in a mosaic — salve lucrum, or “hail profit” (CIL 10.874).

Photo 11.2

Chapter 11 of In Stone and Story makes mention of Quinctius Valgus and Marcus Porcius — Pompeii’s earliest mayors, or duoviri. One inscription dedicated to them is shown in figure 11.2 of that chapter. This photo shows the other Pompeian inscription dedicated to them — this one hanging in the corridor of the “theater section,” honoring them for their benefaction to the people.

Photo 11.3

When Pompeii’s macellum (or “market”) was restored after the eruption of 62, these two statues were placed front and center in the restored complex. There is some debate as to who the male and female figures are, but the best guess is that they are the husband and wife who sponsored the restoration of the macellum.

Photo 11.4

A tomb honoring Gaius Munatius Faustus (who is discussed together with his important wife Naevoleia in chapter 19 of In Stone and Story) displays a boat at sea, probably illustrating how Faustus had made his money in the shipping industry.

Photo 11.5

The significant thing to notice in this photo is the extent to which steps adjacent to the entryway of Julia Felix’s country club (which takes up the whole block of insula 2.4) extend relatively far out into the street. Town officials generally wanted to ensure that traffic would move effectively through the town. The fact that these steps would have interrupted the smooth flow of traffic along one of the town’s most important streets suggests that the household must have had significant influence with the town officials.

Photos 11.6 through 11.9

Chapter 11 of In Stone and Story highlights the significance of the Augustales. These photos depict a few more of the archaeological evidence of the Augustales in the Vesuvian towns.

- Part of the interior of the so-called College of the Augustales in Herculaneum is shown in photo 11.6, and an inscription in the interior remembers a dinner in honor of the emperor, paid for by two brothers (photo 11.7).

- The tomb of Gaius Calventius Quietus remembers him to have been an Augustalis, and displays this graphically through the use of a wreath (photo 11.8); another wreath was displayed on the other side of the tomb as well. (Note that someone with the same name stood for civic election during the Neronian period, probably the son of the man memorialized here. It is possible, then, that the father had been a slave who earned his freedom and became a prominent Augustalis, and that his freeborn son was then free to enter political office — something that the father could not have done if he had been a slave at any point in his life.)

- In photo 11.9, a house is shown to display a wreath above its entryway, probably signaling that an Augustalis lived there and wanted everyone to know this prominent aspect of his status.

Photo 11.10

Boats were a significant part of the economy of the Vesuvian seaside towns. One boat was recovered from the bay of Herculaneum, as depicted in this photo. The boat was more than thirty feet long and had six oars, three on each side. Probably the boat needed four people to navigate it: one person at the rudder, and three people at each pair of oars.

Photos 11.11 and 11.12

In Herculaneum, the so-called House of the Stag overlooked the sea, having a prominent place on the ancient shoreline. The first of these photos shows something of what that might have been like, although the view now looks out onto the high wall of volcanic debris that entombed the town during the eruption (photo 11.11). Photo 11.12 is the reverse view, showing the position of the house over the town’s shores.

Discussion Questions

- Chapter 11 of In Stone and Story discusses the interaction between money and social influence in the ancient Roman context. How are these ancient realities navigated in New Testament texts? How do they compare to your own cultural situation?

- This chapter discusses mythical stories in frescoes to analyze the relationship of money, influence, and power. How does the “mythos” in your context reflect, deflect, or refract widely held positions on money, influence, or power?